Thinking About Getting Into is a newsletter about cultivating interests.

In May I landed in Vienna with a ticket to the ballet, a hotel reservation, and not much in the way of an itinerary. I decided that I would make things up as I went along my seven-day solo trip. It is not in my nature to do so.

I am a planner. I think constantly about the future, and my near-constant anxiety about it is what propels me forward. My mind is a crisis comms firm; I am always thinking of worst-case scenarios—within reason—and what I need to do should they arise. This is why I laugh when people tell me that I have a preternaturally calm disposition—the secret isn’t that I live with the belief that everything will work out, but rather that I am always planning, always testing solutions to potential problems. I am always treading water, and I rarely head back to shore. I figure this is the most efficient route for me to get to where I feel I need to be.

You might suppose that this would make me the type of person to go on vacation with a dense to-do list timed by the hour—and indeed, for past trips, I had constructed such lists. But consumed by work, the drama of turning 30 the week prior, and some psychic impediment I felt to planning, I just couldn’t do it. And so I landed in Vienna not quite knowing what I was going to do.

There are risks to this approach, of course. There’s the threat of wasting time, of not optimizing one’s time and seeing all the sights that one should see in a city where you’re not guaranteed to ever return. There’s the prospect of simply not knowing what to do without the security blanket of having planned ahead. And there is, of course, the fear of missing out on some event or activity you might have been able to partake in had you more foresight.

On my first day, I landed around 11 a.m., having slept maybe four hours cumulatively on my redeye; I took the train into the city center and maneuvered myself to my hotel. The seven-minute walk seemed longer in my sleepless state. My skin felt dry, and I squinted in the afternoon sun while wearing my eyeglasses. When I was finally able to deposit my suitcase and collapse onto a hotel bed, I resisted the temptation to rest for too long. In the hotel cafe, I drank a melange—Vienna’s answer to the cappuccino—had some lunch, and set about to walk the city with no accompaniment but my own thoughts.

I do not often keep my mind and ears open to the world around me; in New York, I find a constant companion in my AirPods as I move myself from location to location. I feel a need to multitask; if I am simply transporting myself, I may as well also listen to an audiobook or catch up on the news or—in moments of more delicacy—listen to a playlist or album. But this has a dampening effect on one’s experience of their surroundings, and especially in an unknown city, such a shield becomes a dulling instrument.

So I walked alone, and I heard a piano practice streaming from the upper windows of a music school, the clear timbre of horses’ hooves as they clopped through the historic city center, and scattered parts of conversations in German, French, and Spanish. I made my way through museum after museum, reading plaques and observing the way that others observed their surroundings. I had thought, before my trip, to take a spin around TikTok, taking note of all the city’s offerings that its prior visitors had deemed most essential, but I considered the possibility that what those travelers sought might be different from what I was looking for.

The truth was that I didn’t have any particular aim—and that was my entire goal. I wanted to live, if only for a week, without some ulterior motive or driving mission. I wanted to be able to sit at dinner, taking in my surroundings, without feeling a need to scroll through my phone or turn my face to my book. What does it look like to cease moving through the rudimentary motions of our daily life, spending—shockingly—hours each day on our phones? Without crafting the perfect schedule for exercising, working, maintaining a household, and tending to our relationships? How many of us are spending the time that we do have to do the things that we purport to love doing?

It is an immense privilege to travel; it is not lost on me how fortunate I am to be able to freely visit a city half a world away, and so I want to make the time I have count. And that means, ultimately, understanding what it is that I want to do.

Traveling alone forces you to confront what, exactly, that is. With all elements of choice left up to your own purview, what kinds of decisions do you make? Without work, without the responsibilities of home—what do you find yourself drawn to?

For some people, that choice will involve making as few decisions as possible; vacationing as a means of finding an inner calm on a beach, a poolside, or some other easygoing locale. But I do not vacation. I travel to see the things I cannot see—or hear or taste—at home. On my first night in Vienna, I listened to a chamber orchestra play Vivaldi’s Four Seasons in an 18th-century church. On my second to last night, I booked a standing room ticket at the state opera house to see The Marriage of Figaro. In between, I walked thousands of steps looking at art, traversing palace grounds, and developing a new, burgeoning interest in the Austro-Hungarian empire. I sat in parks and finished Anna Karenina with a glass of wine, sitting on a ledge in front of a reflecting pool, interrupted twice by Austrian men who approached me, asking “Wie geht’s?” and what book I was reading.

Last year, the philosopher Agnes Callard made the case against travel in the New Yorker, arguing that travel “turns us into the worst version of ourselves while convincing us that we’re at our best.” Her argument boils down to this: That people expect travel to have some transformative force, that it leads them to act in ways not native to their given nature, and that they anticipate returning home, if not fully shifted into some newer, enlightened being, then at least fresh and glowing, as if thoroughly exfoliated. Travel, Callard argues, is instead a means of breaking up the short time that we have on this planet; that it may be fun, but to consider it moralistically metamorphic is to only be fooling oneself.

I do not travel alone because I think that doing so will make me a better person; I do not think that seeing more art and music and architecture and sharing lunch in a museum cafe with a stranger—an older Canadian woman who was also traveling alone—makes me an inherently more interesting person. But I do think that doing so allows me to better understand what it is that I desire when the choices are all mine to make.

I watched a few videos on TikTok of travelers sharing the things that one is not to miss in Vienna, but the varied German names of locales and sites went over my head. Ceiling murals and chandeliers began to blend together. I started to wonder why I should inherently trust these people when I so easily recognize the skepticism I feel when I see videos that appeal to tourists to New York. If I were to follow their directions what might I miss? And what would I find?

There is some discomfort in traveling alone; for every person’s story of communing with strangers and forging a love affair and living life as if directed by Richard Linklater, there are moments of awkwardness and clumsiness. On my second to last day in Vienna I walked to an extensive outdoor market, which Yelp reviewers debated: Was it too touristy or not? Moving through the throngs of people crowded around food stalls and then milling through an ever-expansive flea market, I felt myself growing overwhelmed. I looked at antique still-life paintings that had no price tags but stayed quiet and left empty-handed; I’d rather avoid the embarrassment of revealing my American English.

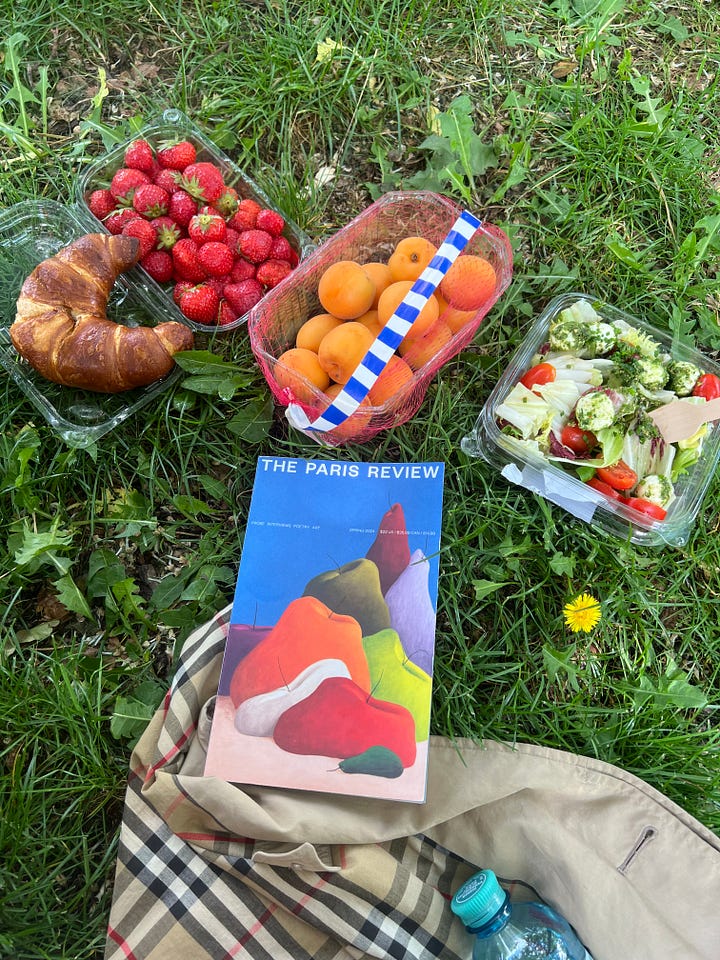

But it is impossible to avoid embarrassment when you are consciously trying to do just that. I sought anonymity in a small grocery store, where I loaded up a basket with a number of items I could eat alone in a park: clamshell containers of apricots and strawberries for €3 each, a plastic-wrapped cheese and red pepper sandwich, a tomato and mozzarella salad. It was only after I had completed my self-checkout that I realized that I hadn’t a fork with which to eat the salad. I looped back through the store, fruitless in my search, and prepared to make my final exit before a cashier stopped me, confused by my confusion and made all the more perplexed by my question, “Do you have a fork?” She directed me to go to the back of the store, where I repeated my question to the women at the deli counter, who delivered—after some conversation between them—a decisive “no.”

I ambled back to the exit, where the cashier paused me again, starting in German before asking if I got what I needed. I didn’t, but it was fine, and I would figure it out. I ended up swiping a wooden utensil from another food market I passed on my way to the park and nested it deep in my pocket. I was severely underprepared for a picnic, but once I found a friendly enough path of grass, I splayed my trench coat out as a blanket and dug into my paper shopping bag, where I found multiple items covered with the glossy sheen of leaked-out salad dressing. I didn’t have a napkin.

When you travel by yourself, you are left to shoulder minor upsets and disappointments yourself. It is your choice alone to figure out how, exactly, you can and should react. I tore apart the paper grocery bag and used it to sop up the oily residue where I could; I transferred some items—chocolates and wafer cookies—to my tote bag for later. I ate my food slowly, watching as parents walked children through the park, as couples paused on benches, and others, alone, moved through their own worlds. I didn’t touch my book, and when I finished eating, I carried my trash in both hands in search of a receptacle.

It is easy to imagine that the people you see in different cities live great and beautiful lives. I wondered at the young adults gathered on the sunny lawns of Burggarten and at the businessmen sharing a meal at the same restaurant as me, a privacy bush dividing us but their English seeping through it. I thought about the older women I sat with as I waited silently for a concert to begin. I thought about the couples I saw walking through the halls of early Renaissance portraiture and the woman working with oil pastels in one of the salons of the Belvedere. What had brought them to be in the same place, at the same time, in which I found myself? And what had brought me?

I am trying, now, to give myself more space to think such things in the constricted confines of my everyday life. I will take the long way to get to where I need to be if time allows. I will step out into the world without a stream of voices or instruments playing constantly in my ears. I will go to a museum or the ballet or the opera—as I am already wont to do—and feel the assurance of my choice. I am here because I want to be. What brings you? ▲