I’m thinking about time and about consumption lately and about how—now past my twenties—I want to develop more discipline. I am in this period of life where my responsibilities center only on myself (and my cat), and that means I have more time than perhaps I will ever have to devote to writing and reading and engaging with art that I find interesting, impactful, or meaningful. It is quite easy to say that time eludes you when the reality is that time must be captured and shaped into being; passivity yields nothing more than a placid continuum. All this is to say that I’m trying to be more intentional, and that means I intend to show up more here with my personal writing and more cultural news digests. I’ll be taking a hiatus from interviews for the time being to devote more energy to these projects.

So, more to come—and in the meantime, I’ve got the news you need to be cultured. Today we’ll discuss a new promotion at American Ballet Theater, the state of arts funding, updates in the world of opera and classical music, and more.

What is the state of arts funding? Overall, not great! But there is some good news. After months of threats—and corresponding protests, including those led by the New York City Council—the Adams administration has reversed its decision to cut more than $100 million in funding for museums, cultural institutions, and libraries. The 2025 Fiscal Budget will restore $58.3 million to all three NYC library systems and $53 million to support more than 1,130 cultural institutions. Gothamist adds that according to its sources, the Adams administration has also agreed to allocate “$43 million annually for the libraries in future years”—a considerable concession, given the mayor’s historical lack of support for the institutions. Adams had previously suggested that the library systems tap their endowments in order to stay afloat and maintain Sunday service; however, those funds are typically used for special programming…not to provide their core services. Those numbers may seem substantial, but the New York Times puts things into perspective: A line item in the NYPD’s $6 billion budget sets aside $39.8 million to buy two police helicopters……….But the libraries are asking too much I guess!

Things are looking so much worse in Florida, where Governor Ron DeSantis has vetoed the state’s ENTIRE arts budget—$32 million set aside for arts grants—for deeply stupid reasons. As the Tampa Bay Times reported, DeSantis suggested that taxpayer dollars were going to “sexual” festivals, like the Orlando International Fringe Theater Festival, which has gone on for 33 years and includes musical and theater performances, kids programming, art installations, and more. Its website reads: “The nature of a festival is to be welcoming and inviting to all. The goal of Orlando Fringe has always been to bring diverse elements of society together and have something for everybody. Truly, anyone can Fringe. And we welcome all with open arms.” State representative Anna Eskamani, who attended the festival, told the Tampa Bay Times that it was not “sexual.”

Meanwhile, in California, a coalition of union members, parents, and former superintendent Austin Beutner has accused LA Unified school district of misspending the $77 million that voters approved to go to arts education. Basically, that group has suggested that the school district is using that funding to replace its existing budget for arts education and funneling that original budget toward other purposes—in effect, making no difference at all in terms of how much the arts get funded. Proposition 28, the ballot measure that approved these funds, increases arts funding at schools proportionally to enrollment; an analysis of 12 impacted schools shows that nine of them saw no change in their arts budget before and after the implementation of Prop 28 and increased enrollment. Just three of the schools increased their arts budget, but in some instances, it was not at all proportional to the amount that enrollment increased. There are also some issues of interpretation with regard to what an arts budget should cover. Superintendent Alberto Carvalho has, in response, said that the budgets of some schools will be “adjusted” next year, per the LA Times, but he does not acknowledge any wrongdoing.

What do we lose when we lose arts funding? The loss is practically incomprehensible. Last May, the New York Times examined this question and found that it can be hard to quantify—though researchers at Texas A&M have found that an increase in arts education leads students to score higher in writing, empathy, and academic ambition, and see fewer disciplinary infractions. The arts make people more well-rounded, accepting, and engaged in their communities…but these are not benefits that have obvious economic translations, and therefore they are not prioritized in budgets.

We are now in an era in which generative AI—which is decimating the environment with its energy costs (a problem we saw with the crypto craze, too…)—is threatening to cut real, human artists out of the picture with its derivative, shitty images. Art should exist and be supported for art’s sake, though sometimes, people in power need additional justification. Some profess that studying the arts (including the liberal arts) will be the way for people to succeed in tech in the future; if a large language model is supposed to understand human speech, you must know how to appropriately express yourself in human speech…something that can be a challenge for people who choose to silo themselves in numbers and code. Sorry to the tech bros, but also, I’m not sorry. Read a book. Not a business or self-help one.

I hate the thought of needing an economic argument for arts funding, but those in power seem to see little value for the arts, and when the most popular cultural fare (insert snobby insult of choice here) is trite enough that it could easily be the work of algorithms, then arts exposure and education are more important now than ever.

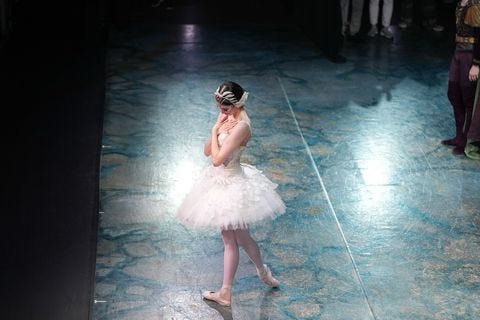

A new swan queen is crowned at American Ballet Theater. Chloe Misseldine, a 22-year-old soloist, was promoted to principal last Wednesday after her New York City debut as Odette/Odile in Swan Lake. It’s hard to imagine a more perfect moment, especially after performing such an iconic role in what I think is a timeless masterpiece. Unfortunately, NYT dance critic Gia Kourlas disagrees with that latter point, suggesting that the ballet, which debuted in its current version in 2000, is “in need of an overhaul.” There is a case to be made, I think, for not touching a good thing.

In 2008, I learned the choreography of Act II via a VHS tape that played on a TV that my ballet school rolled into the studio on a cart; it is special to recognize the movement, which I find perfectly fills the ambitious score. I’ve seen ABT’s Swan Lake at least once each year for the past three years, and I always find a new moment to love: this time, it was the drama of Von Rothbart’s reveal at the end of Act III, with soaring horns, a flash of smoke, and my favorite archetype of classical ballet: a man in anguish, realizing that he has made a mistake. I always cry at least two single tears at the end, after Odette and Siegfried have jumped and the swans fold into themselves as fog covers the stage; I am amazed at how the clash of brass gives way to a slow peal of harp and how the dancers create a sense of synchronized chaos as they dash into new formations. The only part I can imagine revisiting is the beginning of Act III, in which princesses of different nations compete for Siegfried’s hand. The cultural signifiers here aren’t quite as overt as those in the second act of the Nutcracker, but some reinvention there could help the ballet age more gracefully.

Anyway, I saw Chloe perform earlier this season in Eugene Onegin, and she is very clearly suited for starring roles with her expansive lines and evocative expressions. Congratulations!

Museums are continuing to question—and relinquish—their ownership of cultural objects. This week, Cambodia received a shipment of 14 sculptures from the Metropolitan Museum of Art, which were illegally trafficked from the country during the Khmer Rouge regime. It’s the result of years of negotiation and, as Cambodian culture minister Phoeurng Sackona noted, not the first shipment that the country expects to receive. At least 50 artifacts are still at the Met and in other museums in the United States. It’s a big year for repatriation, and we’ve covered this before. Museums across the U.S. are in the process of returning ancestral remains to Native American tribes in response to the Graves Act, and some art museums—like the Met—are contending with their stolen goods from elsewhere around the globe.

Meanwhile, museums and galleries—especially in Europe—are still in the process of returning Nazi-looted art to their rightful heirs. Amsterdam’s Stedelijk Museum announced in June that it would return the Henri Matisse painting Odalisque (1920/21) to the legal successors of Albert Stern, a textile manufacturer who sold his belongings—including this painting—to gain the funds needed to flee Nazi occupation; tragically, Stern and his wife were unsuccessful in escaping Germany. He died in a concentration camp in January 1945, but she survived the war and emigrated to the U.K.

In June, the Louvre put on display two still lifes by Floris van Schooten and Peter Benoit, which had been in possession of the museum since the 1950s, but recently returned to the beneficiaries of Mathilde Javal, from whom they had been stolen during the Nazi occupation. Her heirs, however, donated the paintings back to the Louvre—along with “documents relating to the history of the Javal family, in particular witnesses to the persecution to which they were subjected,” in order to share their full history.

A report released earlier this year by the World Jewish Restitution Organization and the Conference on Jewish Material Claims Against Germany found that multiple countries—including Russia, Spain, and Denmark—have lagged in repatriating Nazi-stolen artwork. It estimates that around 100,000 pieces of art and cultural and religious objects have never been returned to their rightful owners. Getting back these objects, even if their location is known, is not an easy task: Just see the case in Amsterdam of a notary refusing to relinquish a Dutch master painting to its heirs 17 years after a Dutch panel had deemed them the rightful owners…all because they don’t have the right documentation.

The question of repatriation is not a new one, as the New York Times recently noted, pointing to the moment in 1815 when Belgian and Dutch officials came to the Louvre to take back artwork that had been looted during the Napoleonic wars. The return of artworks across Europe did spark the building of a number of museums, including Amsterdam’s Rijksmuseum and Spain’s Prado. It’s an apparent case for giving those with claims of ownership the choice to decide what is the best path for preservation and cultural appreciation.

Of course, that’s also the argument that Greece makes for the return of the Elgin marbles. Now that Labour’s in control, will we see a change of heart—or at least of philosophy—at the British Museum?

Talk about a revival. For the first time since 1671, a theater troupe—the Canterbury Players—are putting on The Amorous Prince, or, The Curious Husband by Aphra Behn, which had been deemed too radical upon its debut. For those of you who opted not to take a Renaissance English drama class in college, Aphra Behn was a playwright and poet born in 1640, 24 years after Shakespeare’s death in 1616. She was the first English woman to earn a living by writing. The story of The Amorous Prince is not far too unfamiliar to anyone who has ever met a straight man: It is about two guys, “Frederik, who believes he can have sex with any woman he wants, and Antonio, who asks a friend to test the fidelity of his wife.” Just throw in an Instagram DM plotline, and you’ve got your next Netflix comedy.

Let’s put this to bed: Maurice Ravel is the only composer of “Boléro,” so says the French court. Heirs of Ballet Russes stage designer Alexandre Benois—who worked on the original production—argued that he should be considered a co-writer because it was a “collaborative work” made specifically for the ballet. Why did they care? Because French law puts art under copyright for 70 years after an artist’s death, and while Ravel died in 1937, Benois died in 1960—which would mean the piece should still be copyrighted. Except that the French court did not buy this argument at all. So you are free to use “Boléro” as you wish!

More women in classical music, please. In the same tradition as many other Western art forms, classical music and opera have histories dominated by white men. But that doesn’t mean that only white men made their mark—often, it is a case of who gets remembered. So it is quite exciting that later this month (July 20 in Montclair, New Jersey, and July 24 in New York), the Teatro Nuovo company is premiering Carolina Uccelli’s 1835 opera Anna di Resburgo—a work that was nearly lost to time that tells the story of a family drama.

Meanwhile, Berlin’s Deutsches Symphonie-Orchester decided to require at least one woman composer included in every concert for its 2023-2024 season. The resulting programming is hardly a 50-50 split, but compared to the usual fare, it is a notable difference. In the fall, NYT notes, the orchestra plans to continue presenting more work by women, and specifically more work by Black women composers. “We want to show classical music to as many people as possible,” director of artistic planning Marlene Brüggen told the Times. “Everybody’s been talking for years about how classical music is losing its audience. Our approach is to use these dogmas or themes to reach new audiences. For God’s sake, not to alienate old ones, but simply to expand.”

These are the 100 best books of the 21st century so far. According to more than 500 people that the New York Times asked, at least. To no one’s surprise, it is very divisive. What I want to know is: Why go with Sigrid Nunez’s The Friend when The Last of Her Kind is right there? ▲