There is a photo I take in art museums. It is not a selfie, nor is it a more deliberate one of myself posed next to whichever painting or sculpture most pleases me. I take plenty of snapshots of artworks that catch my eye—always in addition to their corresponding wall plaque for later identification. But these are not the ones that I look back on to give me a more defined and comprehensive sense of the space I inhabited. What I like to photograph is other people taking pictures, invariably with whatever is the most highly regarded, or identifiable, work of art in the room.

I’m not sure when, exactly, I started taking these photos. Maybe it was on my first solo trip to London during which my solitude took on a far more novel shape than it does at home in New York. Walking through the saturated rooms of the National Gallery, I felt more aware of the parties I shared space with; the families, couples, and friends moved at varying paces, some chatty and others quiet and contemplative—maybe a touch tired or bored.

They didn’t necessarily migrate around the most famous paintings (my personal audience with the Arnolfini Portrait was a private one), but paused most notably at the grandest-seeming works in the space—Paul Delaroche’s The Execution of Lady Jane Grey—or those, at a mere glance, that were the most easily identifiable: Van Gogh’s Vase with Fifteen Sunflowers.

I like to look at the things other people see, to try to gain a sense of what they might be registering at that very moment. Comparison is deeply embedded in my nature; I want to see if there is something I might be missing.

It has become starkly clear that what I was actually missing was not to be found behind the relief of the figures who stood in front of me to take their photos of Klimt’s The Kiss in the Belvedere or Vermeer’s Girl With the Pearl Earring in the Mauritshuis. It was in all of the many things that get overlooked amid a crowd—the other works filling a gallery, the wall text, the details, even, in the masterpiece. I am not saying anything radical here. But it has become increasingly hard for me to move through these spaces without feeling a tinge of frustration and, I’ll plainly admit, the vague discomfort that arises from the awareness of one’s own pretension. With this perspective it is easy to begin to feel that there is a right way to look at art, and few people around you are doing it.

It is perhaps because of this that I entered the Van Gogh Museum—which, in 2019, was deemed “the most Instagrammable tourist attraction in the world” by an analysis of Instagram engagement by the luggage storage company Stasher (go figure)—with some hesitation.

I should say, first, that this perspective is shaped by my good fortune to have seen ample works by the artist. I’ve passed The Starry Night plenty of times in the MoMA, just as I’ve moved through the Impressionist rooms at the Met without pausing at his Irises or Cypresses. This exposure can naturally have a dulling effect on the introduction of new, yet similar stimuli, as much as one may not wish to admit it.

But information is a balm—or even an antidote—to disillusion. And so I took my time reading the wall text, open to hearing something different about an artist who has been so mythologized and stereotyped that a plot point of Doctor Who attempted to reconcile his tragic suicide with his legacy that has placed his artworks, now, on Lego and luxury fashion.

In the museum’s first gallery—filled with several of Van Gogh’s 36 or so self-portraits—you could forget that the artist was just 37 years old when he died. There is something about portraiture that, when rendered in another era, can refuse to translate to our contemporary understanding of age. With his auburn beard and straw hat, Van Gogh is unplaceable, but certainly not what we’d consider today to be a still-young man. A simple timeline in this room brings this context: that Van Gogh decided to be an artist at the age of 27, spent the next few years learning how to draw, and then paint. In 1888, he painted Sunflowers, had a friendship breakup with onetime roommate Paul Gaugin, and in the aftermath of their fight, cut off his own ear. In his last year of life, 1890, Van Gogh painted an average of one painting a day. Before August, he was dead.

I was halfway through the next gallery when I started to feel lightheaded and scurried back down to the cafe for something of substance—which, due to minimal options, was a slice of apple pie and a Nespresso. I wanted to make sure I had the presence of mind to continue in the way the museum seemed to demand of me.

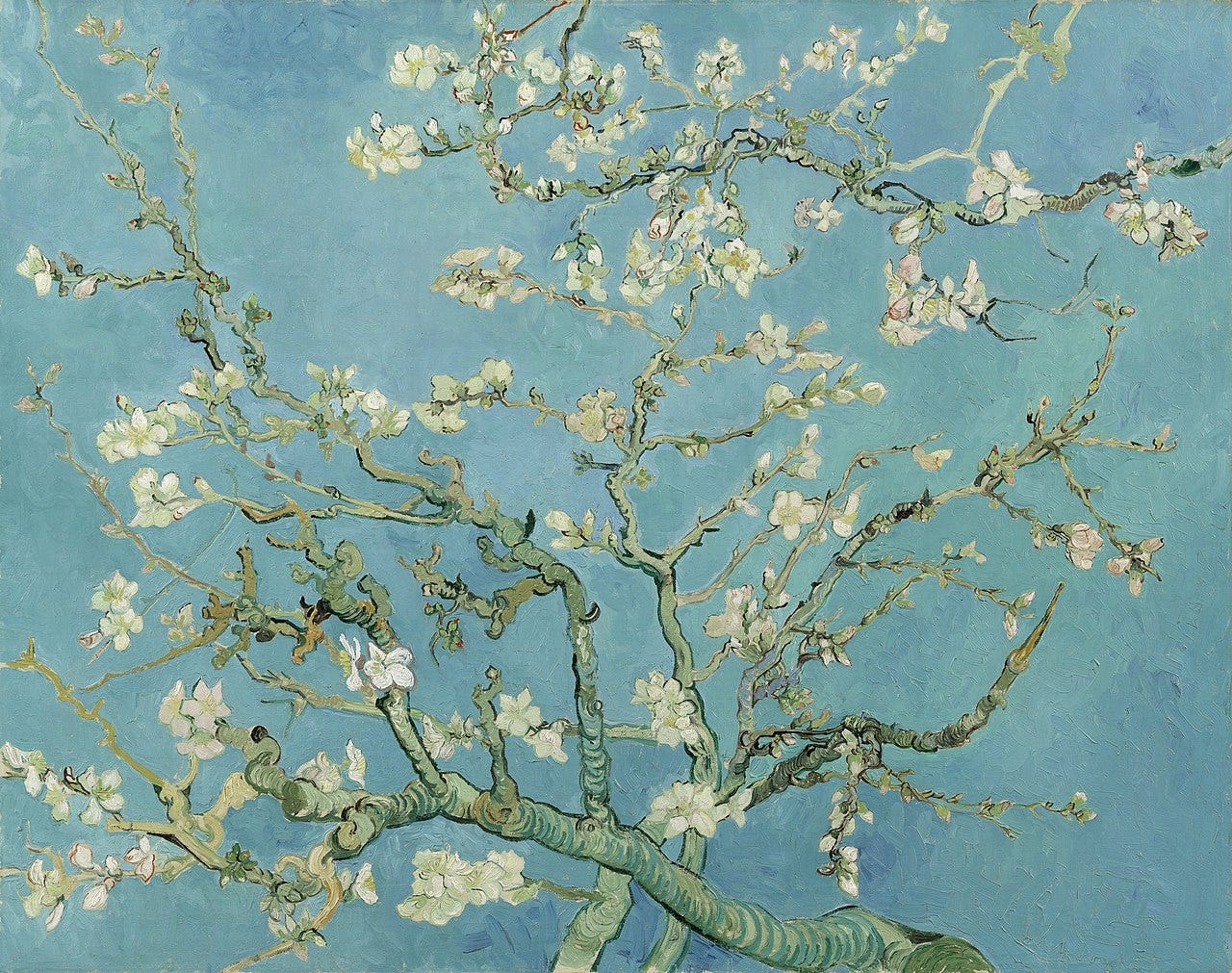

There was a lot that moved me in the Van Gogh Museum, actually. It was his brother Theo’s handwriting printed on the wall, “Beste Vincent” and the newfound knowledge that he died just six months after his beloved brother; his widow, Johanna van Gogh-Bonger, is the reason we know Van Gogh today. It was the wall inscription next to the large and expressive Almond Blossoms, finished in February 1890—a gift to his brother and sister-in-law upon the birth of their son, Vincent. It was “perhaps the most patiently worked, best thing I had done, painted with calm and a greater sureness of touch,” he told Theo.

I approached Tree Roots without thinking much in particular about the colorful, cataclysmic painting, other than the fact that it felt a touch more crowded and unlawful than the artist’s other work. I unconsciously raised my hand to my mouth when I read the last sentence of its label: “The painting remained unfinished; he shot himself in the chest that very afternoon.”

“Is anyone else getting this?” is a crazy thought to have about one of the most famous artists in history. But it is a testament to an artist’s work—and that of historians and curators—when what is understandably a tourist attraction retains emotive power despite its crowds, the commercialization of its gift shop (I did buy several things), and, of course, the concentration of people around those most recognizable objects. Here, it was Sunflowers.

Is there a right way to look at a painting? I would say certainly not—to be prescriptive is to curtail what is a very personal and individual experience. Still, the Tate Britain published its own guide on “slow looking,” recommending 10 minutes per artwork as a good starting point. A 2017 study determined people spend an average of 33 seconds.

There has been much recent discussion of the habits of museum-goers and the ways they interact with their surroundings. A tourist visiting Florence’s Uffizi Gallery recently damaged an 18th-century oil painting while mimicking the pose of its subject, Ferdinando de’ Medici. Another tourist in Verona broke a Swarovski crystal-covered chair by the Italian artist Nicola Bolla in Palazzo Maffei after pretending to sit on it for a photo (and then actually crushing it). “Sometimes we lose our brains to take a picture, and we don't think about the consequences,” museum director Vanessa Carlon said in a statement.

Still, not all museum professionals have turned against the selfie. Tate Britain director Alex Farquharson recently told The Times that he encourages visitors to take photos (even selfies) and compared the act to curation: “People are making a choice when they’re taking photographs and sharing them on social media, in the same way they did when they bought a postcard, and still buy postcards.” (Tate chairman Roland Rudd, meanwhile, just announced plans to create a £150 million endowment fund for the museum to acquire new artworks and improve its garden, which he called “awful.”)

The Louvre also officially opened its design competition for its Nouvelle Renaissance project, which aims to resolve its overcrowding issues with a new entrance and a new room specifically for the Mona Lisa that will give visitors more personal access to contemplate the painting, with timed entrances. (Here, I’ll admit that, at 21, I did speed-walk through the Louvre in order to lay my own eyes on the painting, a manic moment upon my first time in continental Europe).

The reason I take the photos I do in art museums—the ones of other people, that is—is to remind myself of a few things: that I was there, that art has the power to drive people to paparazzi-like postures, and that the crowd will pass, and as long as I wait a bit, I’ll see more people part in front of me, their photos secured. Then, I might be able to really see—the brushstrokes, the humanity, and the bewildering odds for something of such beauty to come into creation, and the rarity of my opportunity to behold it for myself.

Below the paywall, your weekly news items, rapid-fire style:

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Thinking About Getting Into to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.