I previously told you about American Ballet Theatre’s Crime and Punishment, which is on at Lincoln Center now and will premiere at the Kennedy Center next year. Tonight, I saw the world premiere. I felt it was only fair to share my thoughts with you. [Spoilers—for both the novel and the ballet—are ahead.]

Helen Pickett’s Crime and Punishment, a ballet inspired by Fyodor Dostoevsky’s 1866 novel of the same name, opens on the peasant population of St. Petersburg. They are a huddled mass, anonymous as the stage lights brighten slowly, and they expand, militaristic, into uniform lines and formations, dancing in unison; they maintain some rigidity in their structure yet stretch their limbs, and bend into abstract shapes, not unlike those found in more modernist pieces by Balanchine. They are machine-like and evoke some sense of near-oppressive heterogeneity, alike in their focus. And then, when they break apart, a singular figure is left in the center of the stage, writhing.

It is a strong start to the ballet, which follows a story that, when published, painted a picture of the challenges of then-contemporary life. Five years before the publication of the novel, reforms enacted by Czar Alexander II ended serfdom in Russia. Thinkers of the time debated how a better society may have formed from that point forward.

There seems, in Pickett’s introduction to this story, a suggestion that we may gain a sense of the tension between the individual vs. the masses or how the disadvantaged are at least unified in their perseverance amid their suffering.

And then the ballet abandons those suggestions altogether and pushes forth an overly detail-driven narrative that, in its fastidious attention to plot, seems to miss the opportunity that dance presents as an art form over opera or film or drama. What results is a musical, and a halting one at that, which substitutes vocal performances for pantomime by individual characters, as all the other players pause and watch, seemingly trying to determine what it is they really have to say. This is the challenge that Pickett faces through her own work; the choreographer cannot pull a compelling thread from a work of fiction that contends with big-picture ideas about society and wealth inequity, free will and destiny, redemption and forgiveness, nihilism and Christianity.

The ballet, in total, has 22 scenes, including a prologue and an epilogue, each of which depicts a small vignette that carries the plot forward. We see Raskolnikov—our protagonist, who at the start of the story has committed two murders—celebrating the publication of an article he has written. We see a street accident that leaves a man dead. We see Dunya, Raskolnikov’s sister, announcing her engagement to the pompous Luzhin. Through this all, we are introduced to 13 named characters and three unnamed, plus the “citizens.” They are in the bar. They are on the street. They are in Raskolnikov’s barren room where, when alone, he thrashes his body in torment.

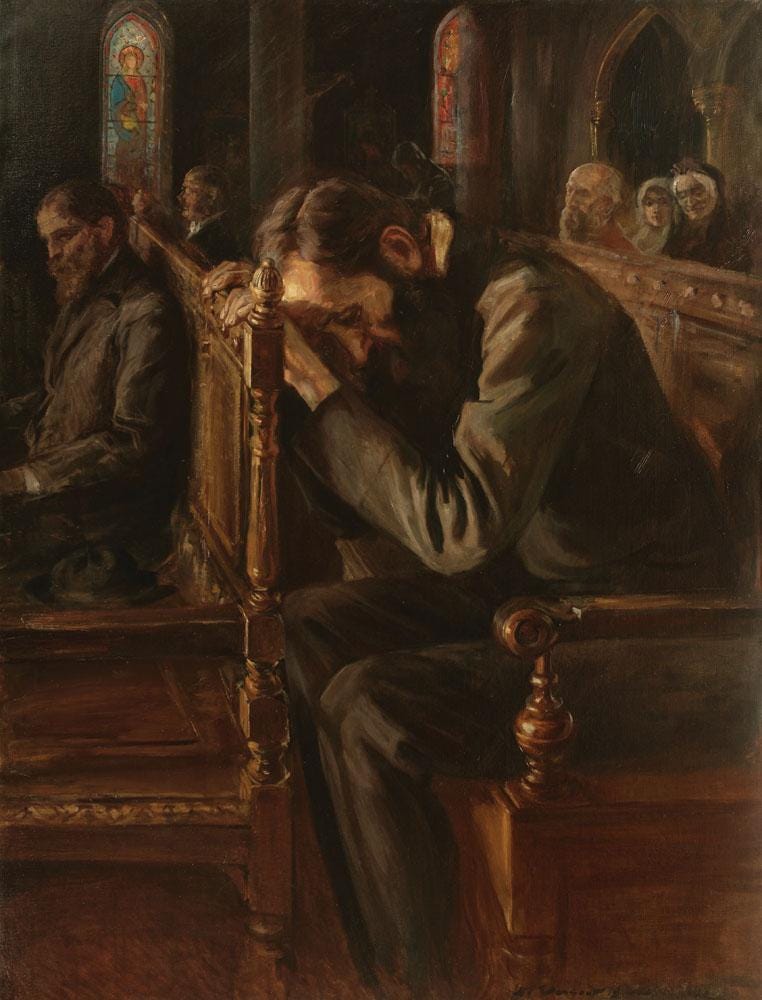

There is a lot of self-flagellation in Crime and Punishment, the ballet. In fact, the choreographic tenor of the ballet tends to oscillate between different kinds of movement popularized in contemporary classes; there is much stretching of the arms to the heavens. There is much whipping of the limbs in semi-controlled chaos. The chin is often pointed downward, the dancer expressing the outward depiction of deep, inner anguish.

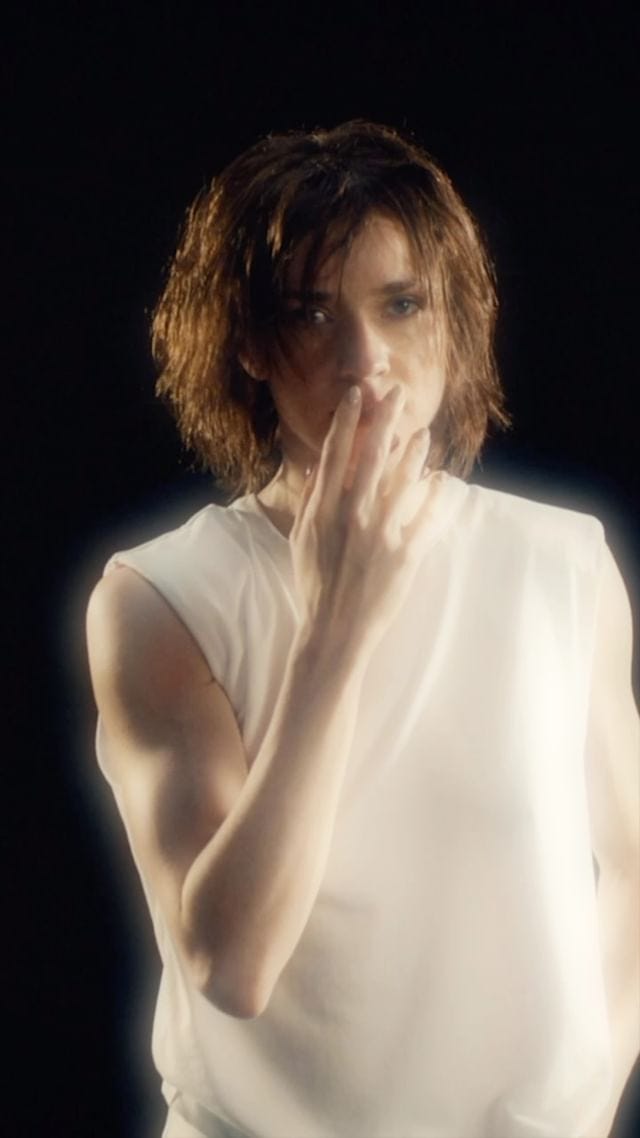

This approach determines much of Raskolnikov’s oeuvre. It is a gender-neutral role, debuted by the incredibly talented Cassandra Trenary, who clearly poured herself into what she was given. The role is not a testament to her versatility and artistry as a dancer, through no fault of her own; the steps she is given largely stay at the same level of impact throughout the whole piece, to monotonous results.

When we return to the scene of Raskolnikov’s crime at least three times through the ballet, the character mimes the murder of pawnbroker Alyona Ivanovna and her sister Lizaveta Ivanovna with similar frenetic energy. Curiously, there is minimal contact made between the dancers in these scenes; instead, Raskolnikov swipes through the air with an imagined facsimile of an axe. Meanwhile, on a transparent, overlaid screen, we see two actors dressed in cartoonish costumes of the elderly women, repeatedly expressing shock and horror at their own murders. It is not entirely a linear film; intercut, there may be the image of an unblinking eye or a hand holding the pocket watch that Raskolnikov stole from the women. But then, there is a flow of red down screen actor Lizaveta’s face, disrupting the black and white hued video and perhaps trying to distract us from the fact that there is not really that much going on onstage, not even a kind of twisted pas de trois.

This is not the only visual aid in the ballet; scenes start with a single line or two of text emblazoned in the upper right airspace of the stage. After the ballet’s striking opening, for instance, we find our main character in his room. The stage text reads: “Raskolnikov wakes up in a sweat. There has been a murder.”

I am not opposed to such a cue; this first one, while certainly not swiped from Dostoevsky’s text, does set up a bit of psychological tension, which the ballet does not fully realize. We do see, early on, moments of Raskolnikov’s paranoia tempering the way he moves through the ballet, but this is eventually overshadowed by the density of the plot that has made its way into this adaptation. In this way, Crime and Punishment suffers from the same affliction as ABT’s previous recent novel adaptation, Like Water for Chocolate; the latter, while mired in narrative details, does still find opportunities to create striking and memorable dance moments, a task with which former remains unsuccessful.

Where Crime and Punishment largely disappoints is its insistence on treating dancers not as members of a company but as individuals who present their own monologues, pause and watch the other cast members do the same, respond, and so on. There are few opportunities for dancers to move in synchronicity or even to dance around one another in an ongoing conversation. One of the ballet’s loveliest moments, a pas de deux between Dunya (Christine Shevchenko) and Raskolnikov's friend Razumikhin (Calvin Royal III) alludes to what could have been, if only such choreography permeated throughout the production.

In certain ways, Crime and Punishment lacks confidence in the narrative it is trying to convey and in the audience it anticipates. The stage text at the start of every scene starts to feel tired after the first five times or so and doesn’t always offer clear context as more and more characters are thrown into the fray. Moments of stage-setting in between scenes continually slow the story to such a degree that it’s impossible to feel propulsive; Isobel Waller-Bridge’s score, while lovely, does little to help in this regard. There are moments of beauty and alarm in an overall unmemorable score that seemed more suited to a movie, which may not hinge its pace on a soundtrack as much as a ballet must. There are moments of clarity displayed in both sets and costumes, though there is a great unevenness in the aesthetic whole of the production that, at best, feels a bit lackluster and at worst, decidedly distracts from the dancing; a barren stage, outfitted just with Raskolnikov’s bed and a traveling spotlight, makes an odd setting for Dunya and Razumikhin’s charming pas de deux.

Can Crime and Punishment work as a ballet? Ultimately, I think it can. But this production is not successful in doing so. And I think this reflects a general challenge across the ballet world for choreographers to reimagine the story ballet for the 21st century. Not everything is going to be Swan Lake. In 2024, not everything should be Swan Lake. But I’ve been thinking about what makes the great classical ballets work. Music is critical, of course. So, too, is choreography, though different companies, of course, have their own takes on the original source material that might stem from Petipa or Ivanov.

I think there is a dramaturgical challenge that might be the greatest hurdle for choreographers today; it is a risk, in telling an existing story, to strip something down to its essentials and trust that it will still work. This fear seems to lead to an overreliance on literal interpretation, and that interpretation offers little room for dance to play its figurative role. Pantomime, of course, has always been a part of ballet. It’s how we know about the curse in The Sleeping Beauty and about the Christmas tree, before we ourselves see it, in The Nutcracker. But a production carried out almost entirely by pantomime is one that expresses a failure of imagination and a limiting fear of abstraction.

Some have been successful in this kind of narrative reimagining. I think of Akram Khan's awe-inspiring version of Giselle choreographed for the English National Ballet; while using the classical ballet as source material, Khan takes all of its components apart to invent something that feels fully new and arresting, that evokes pain and heartache through a vision that strips back the romance of the original to make something more raw and visceral and cinematic in its gestures and presence. It is a beautiful production that does not hinge its success on its production value.

Ballet, after all, is about the dance. All the other parts of it are important, but when the most memorable aspect of a production is a special video effect, then we miss the forest for the trees.

In the epilogue of Crime and Punishment the ballet, we see Sonya, the moral force of the novel, visit Raskolnikov in his Siberian prison. They dance together, but barely. “There is hope,” the program states, describing this conclusion, depicting Sonya’s forgiveness and Razkolnikov’s atonement. But there is little inspiration to be found in the pair’s small, clutching movements.

“They were resurrected by love; the heart of each held infinite sources of life for the heart of the other,” writes Dostoevsky in the final pages of his novel. The ballet, meanwhile, ends with the pair just steps away from the human-sized cage from which Raskolnikov has been temporarily freed to engage with Sonya. This is not a crescendo nor a revelation, but at most, another tick forward of the plot. Sonya has forgiven Raskolnikov for a crime that had not been committed against her. What does that mean for her? For him? For the world in which they find themselves and survive in against all odds? They lean against one another. The stage fades to black. ▲